In 1916, Fort Worth built a Municipal Beach, directly where the Nine-mile Bridge connected to the west shore of Lake Worth. It was a huge success. By 1920, over a hundred thousand bathers patronized the beach each season. It was so popular that a bus line from Fort Worth called the Fort Worth Auto Bus Company took passengers from the end of Rosen Heights line to this beach.

Thanks for helping to make the Casino Ballroom New Hampshire's Premier Entertainment Facility. Get Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom, Hampton Beach, NH, USA setlists - view them, share them, discuss them with other Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom, Hampton Beach, NH, USA fans for free on setlist.fm! Thanks for helping to make the Casino Ballroom New Hampshire's Premier Entertainment Facility. Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom tickets Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom - See it Before it's sold out! Ticketsinventory.com makes it easy to find Sold out Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom tickets in addition to luxury seats for Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom; besides, we are your first destination for New Hampshire hot events appearing in Hampton and your favorite events taking place in Hampton.

In 1927, a company out of Bellafontaine, Ohio called A.J. Miller & Co. wanted to take advantage of this new Lake. Seeing the enormous groups of visitors and bathers that flocked to the Municipal Beach each summer, entrepreneurs, E.A. Albaugh and French Wilgus had a plan to make Casino Park the largest amusement park in Texas and the Southwestern United States. The company leased the very same ground from Fort Worth, and sunk over a $1 million into this playground, which consisted of rides, a midway, a boardwalk, bathhouse and swimming area, and a huge ballroom. Over 125 carpenters were at work at any given time during construction, using more than a million feet of lumber. Casino Park (also known as Lake Worth Amusement Park) would not only cater to bathers and visitors, but would attract oil magnates, wildcatters from west Texas and cattle barons of the Southwest.

Casino Park was renowned for having The Thriller, the largest roller coaster in the southwest. It was almost a mile long, with humps that varied from 14 to 72 feet. Three trains, each carrying 24 passengers were operated. It was one of only three roller coasters in the entire country equipped with the latest safety devices; wheels of the cars rolled between, under and overhead on the track so that a derailment was almost impossible. Mr. H.S. Smith, engineer for the John A. Miller Company of Detroit directed construction of the monster 'ride'. Casino Park also had some unique rides, such as Bluebeards Castle and the 'Bug-a-Boo' tunnel train. Amazing stunts like high diving horses complimented the Midway. There was even a 300-lb caged gorilla named appropriately Big Boy. Other familiar and popular rides such as the 'Tilt-a-Whirl', 'Dodge-em' and Merry-go-round complimented the Park. The Midway had the usual concession stands and games, such as the ring toss and shooting gallery. The park also had the largest boardwalk west of Atlantic City, made of wood and over 400 feet long. A swimming area, complete with a sandy beach and bathhouse drew in those people who wanted to cool off in the summer months. Motorboats could be rented for scenic tours of the lake.

Casino Park held an annual beauty pageant, and on the Fourth of July, the Casino would draw crowds of well over a hundred thousand strong to celebrate and watch the fireworks display put on by the late W.A. Engelke. Mr. Engelke, owner of the Pan American Fireworks Co., in Samson Park, was known throughout the world for his talents in fireworks displays. The park season began each year on May 1st and ended on Labor Day, with bus service that continued to transport the public to this park for several years.

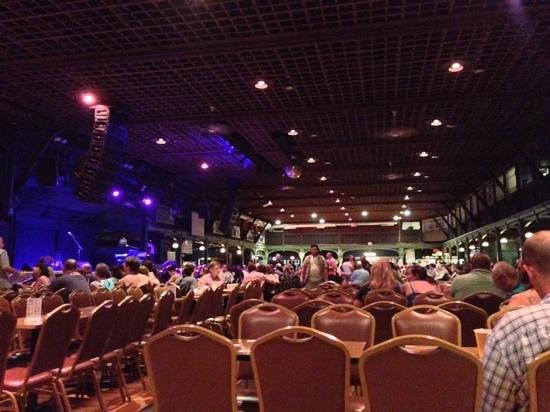

But by far, the center-point and most long-lived attraction was the Casino Ballroom. At over 31,000 square foot, it could seat 2,200 people for dancing and a hot meal for $2 per person, total. It attracted the biggest bands in the country and had it's own nationally known radio show. It had a beautiful smooth floor made of 2-foot x 2-inch strips of solid oak. There were two bars and a full service kitchen. Underneath the ballroom, no space was wasted. On one end, there was an icehouse owned by the Fort Worth Ice Company. On the other side was the boiler room, and in the middle were the tracks of the bug-a-boo train. From the late ‘20s through the ‘50's, the big bands flourished, the top names played at the Ballroom; Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller, Frank Sinatra, Herbie Kay, Rudy Valle and Ted Weems, to name a few.

Casino Park was also to compete with the Lake Como Pavilion, which had its' pavilion and amusement park rides. But the aging Pavilion, built in 1889 was small and isolated, built more to attract streetcar passengers along the Arlington Heights Line route, and the numbers of people dwindled with the burning of the 'Ye Arlington Inne.' It could not compete with this new and larger amusement park.

The small community of Lake Worth suddenly had a business in it's midst that carried over 500 jobs. The population of Lake Worth wasn't even enough to fill the positions. The population of Lake Worth began to increase as people sought housing close to their place of employment. A land development called 'Indian Oaks' then took off full steam with the help of philanthropist G.T. Reynolds. Each street name featured the name of an indian tribe.

Casino Park was a place that launched many a career. Harry Beason, who grew up in Lake Worth recalls, 'I started off raking the beach sand in the swimming area. Then I was 'promoted' to the icehouse, then the boiler room, both of them under the ballroom. Harry Beason recalls an amusing memory from those days. 'The bug-a-boo cars were driven by mules, and they always seemed to stop in the dark of the tunnel. Couples would take advantage of the dark to become romantically involved. It was my job to prod the mules so that the ride wouldn't back up'. Interestingly enough, Beason became Sheriff of Lake Worth in his later years.

Life began for Constable Paul Meador when he was nine years old. That's when his family moved from the sleepy community of Azle to Lake Worth. With the Parks' boardwalk, roller coaster, rides and dance hall, he remininced in an interview for the 1984 Sentinel: 'It was like living in a carnival. What kid wouldn't like it?'.

Another resident, Bud Irby, began as a busboy in the ballroom, and eventually became a partner in the Lake Worth Amusement Company, the owners of Casino Park.

The 1920's

The first manager for Casino Park was E.L. Furnas, and he had his hands full.

In only it's second season, Fire destroyed much of the Park in 1928. On June 17th , 6:20 a.m., fire followed a blast on the boardwalk. Fanned by high winds blowing off the lake, it quickly got out of control of park employees, who attempted to stem destruction with four chemical carts. A dozen fire trucks which raced to the scene, pumped water directly from the lake and succeeded in saving Bluebeards' Castle and the Thriller. The Ballroom, bathhouse and between 25 and 30 concessions were destroyed. Four park employees, attempting to save the ballroom, were trapped and forced to leap into the lake and swim to safety. Big Boy, the 300-lb gorilla, was burned to death. Workers described as almost human the weird cries of the giant beast as flames licked into his cage. 'You could hear the screams of the gorilla for miles' recalls one of Effie Morris' students. Fortunately, the gorilla was given a mercy killing. A cause for the fire was never determined. It must have not been for the insurance, because A.J. Miller & Co went right back, reconstructing Casino Park from the ground up. It cost $140,000 to rebuild. But as rebuilding took place, Mr. Furnas decided to leave Casino Park forever.

The company needed a new manager replacement. Stockholders from the A.J. Miller Company, who had known Smith, asked him to take charge So in the same year, George T. Smith moved to Fort Worth from Los Angeles to take over operations of the Casino Ballroom. In Los Angeles he had been a salesman for ambulances and funeral hearses. . It was quite a career change, switching from the macabre to a rainbow world of dance bands and nighttime merriment.

The Casino Ballroom flourished in the 1920s' with the big bands. The first band to play at the Casino Ballroom was headed by Hogan Hancock. Hancock had a trumpeter in the band that blew with such gusto that Casino owner George Smith found it intolerable. Completely unnerved by the trumpeter's blasts, he gave sharp orders to Hancock: 'You either put that trumpeter in the back row of the band or hide his horn. He's driving me nuts!'. Hancock hastily moved the offending trumpet to a chair completely behind the band. Not too many years later, G.T. Smith was glad to have this young trumpeter back at the Casino, and to pay him a large fee. This time, the trumpeter was heading his own band, and was a star. His name: Harry James!

The 1930's

The park reopened on June 28th, 1930. But instead of being built primarily with wood, many of the major structures were built in a stucco Mediterranean style motif. The 1930's were the heyday for this park, despite the Great Depression of 1929. People who had money, spent it.

Many nightclubs opened along the stretch of Jacksboro Highway, trying to compete with Casino Park. A young lad could make a small fortune in those days, running bottles of whisky to customers at 50 cents each. It was possible to earn $150 a week - a small fortune in those days (roughly the equivalent of $900 today). Women were 50 cents each, or $2 for the night - and plentiful. Although booze and gambling were illegal, either by state or federal law, the strip boomed. The practices were general knowledge, even to law enforcement officials. But rarely would a business be closed; conveniently, somehow the slot machines and booze would ‘disappear' from an establishment as watching eyes loomed nearby. As these businesses flourished, so did the gambler and gangster activity. Jacksboro Highway was beginning to get a reputation.

Nightclubs with exotic names such as The Palm, The Blue Dragon Inn, The Peacock Garden, Gingham Inn, The Showboat, and the Yellowjacket began to dot Jacksboro Highway, creating a strip leading out of Fort Worth. Many if not all of these clubs offered booze and gambling. The establishments were a medley of honky-tonks and high-class establishments, catering to the elite, bootleggers, rogues, rednecks, roughnecks and college kids on the prowl.

The Coconut Grove Nightclub was opened by Earl Hodgkins, son of Jim Hodgkins in 1937, on the same ground where the old Hodgkin's Trading Post was located. Free internet live tv. It is located where the old Coconut Grove Beer Barn stood, at Jacksboro Hwy and Foster. The Coconut grove was the place of choice for musicians to congregate after completing their gigs.

But the Casino Ballroom had to be held above regard. The best of the best performed there. It wasn't just a matter of 'no shoes, no shirt, no service. You had to wear a coat and tie in the ballroom, and ladies wore dresses. And it wasn't a place to fight. To insure this, a group of bouncers headed by former heavyweight boxer Sully Montgomery maintained the peace. Sully was a big man, the toughest of the tough. It was a common sight to see him at the 'ringside' at the end of the boardwalk for monday night boxing. He later became Tarrant County sheriff from 1946 to 1952.

The 1940's

The 1940's were to become the decline of Casino Park. The years of depression were beginning to wear out even the staple customers. Numerous fights between the Casino, the City of Fort Worth and even the State of Texas were more the norm than the exception, With World War II, the casino operated profitless during the winter seasons at the request of the military authorities.

The year 1940 in particular was not a good year for the park. As early as February 6th , Casino Park sought debt relief in court. Then tragedy struck: on the July 4th , 1940 11 p.m., a portion of the boardwalk collapsed, injuring 56 people, 8 seriously. On the same day, a drunk made a fatal mistake and stood up in the roller coaster, falling out as it came out of the apex of the circular ‘loop' of the Thriller. Independence Day was one of the busiest days of the season. The news spread like wildfire, seriously damaging the reputation of the park.

By July 26th, the Casino was to fill out it's season under receivership to avoid shutdown threatened under a temporary injunction obtained by the State Comptroller's office in Austin. It restrained the resort from operating until it had purged itself of $2000 in back taxes. By August 9th, the Casino Park was in bankruptcy. A hearing was conducted for casino manager G.T. Smith. All in all, 22 misdemeanor accounts were filed against him, including operating slot machines without a license. But business went on; by year's end, the City of Fort Worth and G.T. Smith had reached a lease agreement. Casino Park struggled on. G.T. Smith remained until 1949.

By 1941, the boardwalk was torn down. The contract was awarded to Morrow Wrecking Company for $3,250.

On April 8th, 1943, fire destroyed the bathhouse, reducing it to ashes. A cause for the blaze was never determined. Replacement costs were estimated at $15,000, and the city, which now owned the property, had only $6000 insurance on the structure. It was decided not to replace the structure, mainly because it had not been used in quite some time. The Bathhouse had been in a dilapidated condition, with windows broken out and wood boards removed. With the bathhouse destroyed, operation of the beach and swimming area was in jeopardy. On April 16, 1947, Fort Worth took over.

The legal and economic woes for Casino Park continued. On May 21, 1947, the City of Fort Worth filed suit against the Park for delinquent back taxes in the order of $6,917. Smith said that an investigation of the city tax records showed that the Casino was not assessed any taxes between 1938 and 1945, but the city legal department on April 30 had back payments assessed until 1938. Smith said he received only one tax statement, for taxes due in 1946 that he paid.

Asst City Attorney Floore said, 'There were delinquent taxes due at the time the suit was filed in district court on which he had notice.' Floore said the 1946 taxes were not paid until Wednesday; $765.05 in taxes plus $45.90 in penalties. Said Floore: 'If Mr. Smith will pay the taxes owing, the city will dismiss the suit.'

The reputation of Jacksboro highway began to tarnish along the neon 10-mile strip rough-and-tumble, now known as 'Thunder Road'. As a youngster growing up on Jacksboro Highway, Pat Kirkwood scrambled atop the roof of his dad's gambling joint on Saturday nights and assessed the economy by activities along the road below. 'If it was a three ambulance evening, money was a little tight', he recalled. 'but seven or eight ambulances meant everything was OK. People were out spending money and boozing and brawling'.

The Casino Ballroom still survived, with Woods Moore leading the Casino Ballroom orchestra In 1945. In 1948, G.T. Smith retired from Casino Park and ownership was maintained by the City of Fort Worth. Joe E. Landwehr managed the Park for the city until it could find a new owner. Joe Landwehr named Wayne Karr to head the Casino orchestra.

In the spring of 1949, a Trans-Texas airliner having mechanical problems made a crippled landing at Meachum Field. The passengers were informed that there would be a delay of several hours. The unexpected stop was to change the life of one passenger aboard. This passenger was en route from his Alpine, Texas auto dealership to watch the Alpine Cowboys play a baseball game in Wichita, Kansas. The passenger: Jerry Starnes. As he recalled: 'I had heard of Fort Worths' Lake Worth Casino Ballroom and decided I'd like to see it. I took a cab from the airport to see the Casino.' As Starnes arrived, he said 'The ballroom was impressive but I was shocked by the condition of the adjacent lake beach. The old bathhouse was about to fall down. It was a junkyard' Starnes was captivated by the possibilities of a newly equipped beach with side attractions. So much, in fact, he stayed over in Fort Worth, went to city hall and signed a lease to take over Casino Beach.

Starnes gave Casino Beach and the Ballroom a 'second wind.' As Casino Beach began it's first season under Starnes, Ray McKinleys' band played to big crowds at the Casino Ballroom. Told of Glenn Miller being coaxed into that fatal flight by a playboy flyer from New Orleans, McKinley remarked, 'The weather was terrible. Even the birds were walking that day'.

Tommy Dorsey drove up to the Ballroom on Oct 17th, in his newest pride, a $40,000 luxury bus. On tour with his band, Dorsey was living on the bus. His bedroom on this land yacht included a mobile phone, radio and an icebox filled, not with the expected beer, but cans of tuna - tuna sandwiches were his passion. He and his band played that night at the Ballroom. He played 'I'm getting sentimental over you'.

The 1950's

The 1950's gave the Casino Ballroom a run for it's money. As television gained popularity, it slowly ushered out the era of the Big Bands. A new formal opening was given by State Senator Keith Kelly in June 1952. He recalled the pleasures of the old boardwalk and called attention to the new safety features for the new one. The paved quarter-of-a-mile boardwalk is fireproof and will not collapse. Jerry Starnes described the shooting gallery, miniature golf course, roller coaster and mini-train for children. But these were never built.

The 1950's were the apex for gangster activity, with Jacksboro Highway as the center of attention. A 'boot hill' in Lake Worth was an exit for many a gambler or gangster.

Jerry Starnes also had his hands full with lawsuits and squabbles with the City of Fort Worth. In December 1958, when Starnes asked for a new 10-year lease to operate Casino Beach, the City Counsel criticized the operation of Casino Beach operations, and demanded to see their books. They also criticized the city auditing department for not keeping the counsel informed when the concessionaire got into arrears with rent. The company owed the city about $11,000 in back rent and concessions percentages. No rent had been paid since 1953.

The 1960's

The 1960's proved a lull for Casino Beach, and the Lake Worth area. One of the financial partners, Bud Irby, had left the Casino Ballroom after many years and established a 20,000 square foot ballroom on the South Freeway (I-35) called 'Guys and Dolls'. Within a year, the Casino Park owners were looking to sell. Sell they did, and the Ballroom stayed alive in various forms, with music leaning to popular ethnic varieties.

In 1965, the Casino Ballroom was remodeled at a cost of $90,000.

At it's height, the Casino Ballroom covered 31,000 square feet, and 2200 people could sit down for a hot supper and dance to the big bands for $2 per person. But rock and roll bands changed the game. Their fees made it impossible to break even with 2200 people. In fact, it would have required seven or eight thousand people to make the break even point. The break-even areas became coliseums and stadiums. Lake Worth had little to offer. Its entertainment attractions were gone. Its recreational status had been superceded by Eagle Mountain and Benbrook Lakes.

The 1970's

Last tango at the Casino: January 31, 1973

The wrecking of Fort Worth's storied Casino Ballroom began yesterday, with workmen in hard hats first ripping away parts of the roof. Then at 4:30 p.m., when debris rained down from the ceiling had covered much of the dance floor, Jerry Starnes and his partner, Reba Smith, danced what had to be the last dance at the Casino. It was a tribute to the thousands of couples who danced away dreamy hours at this nationally known ballroom on Lake Worth. Empty and stripped of it's carpeting was the Casinos' bandstand where the most recognized bandleaders in the country had stood.

Overhead, workmen from the Hearne Wrecking Lumber Company had already torn away enough of the roof so that sunlight intruded on parts of the dance floor that only the twin rotating crystal balls had overseen for decades. The dappled, multi-colored lights spelled romance.

The Hearne Wrecking Lumber Company estimated that it will take five weeks to complete razing of the Casino Ballroom, which had been ordered by the City of Fort Worth. As the roof was torn away, heavy wooden girders beneath looked almost brand new. Workers were amazed. All salvaged lumber was sold on the spot.

Starnes revealed that the Casino may have been saved had not Dan Blocker, the Hoss Cartwright of TV's 'Bonanza' died last May. Mr. Blocker was prepared to put up $250,000 for repairs to the Ballroom, including costly fire-prevention provisions required by the City of Fort Worth before it would lease the Casino.

Starnes knew Blocker when the TV star-to-be was just a student. Starnes aided Blocker, and two became friends for life. Starnes said, 'I talked with Dan on the phone tree weeks before his sudden death. He planned to fly to Fort Worth for a look at the Casino. He was ready to put up the money. Dan had so much money he had no idea what he was worth. He was a millionaire several times over'.

H Casino Ballroom Seating Chart

To put a final nail in the coffin, G.T. Smith died at the age of 85, outliving the Casino Ballroom by one week. But in retirement, he was not one to dwell in the past. When demolition of the Ballroom began, hundreds flocked to the site for a 'last look' at the ballroom where they had danced away happy hours in younger years. Not G.T. Smith, however. From his home at 3815 West 4th Street, he told Jack Gordon, Fort Worth Columnist, 'I'm not a sentimentalist. No, I won't be going out to the Casino again, ever'. He never did.

Casino Park Inc. Managers

E.C. Furnas, 1928

George T. Smith, 1928-1949

Jerry Starnes, 1949-1973

Joe E. Landwehr, 1959-1966

| Former names | R'naissance Casino Ballroom (1926) |

|---|---|

| Address | 2341–2349 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard Harlem |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1924 |

| Closed | 1979 |

| Demolished | 2015 |

| Architect | Harry Creighton Ingalls |

The Renaissance Ballroom & Casino was originally, when built in 1921, a New York City complex that included a casino, ballroom, 900-seat theater, six retail stores, and a basketball arena. It was located in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan at 2341–2349 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, on the east-side of the boulevard between 137th and 138th Streets. The 7th Avenue frontage spanned the entire block.

History[edit]

The Renaissance Theatre Building, as it was originally named, opened January 1921. It was built and owned, until 1931, by African Americans. It was known as the 'Rennie' and was an upscale reception hall. The 'Renny' held prize fights, dance marathons, film screenings, concerts, and stage acts. It was also a meeting place for social clubs and political organizations in Harlem. They gathered to dance the popular dances at the time, the Charleston, Lindy Hop, and Black Bottom, to live music performed by well known jazz musicians. Jazz artists such as Louis Armstrong, Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Lionel Hampton, Cootie Williams, Bessie Smith, Lena Horne, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald performed at the 'Renny'. In the 1920s the Renaissance Ballroom was known as a 'Black Mecca'. It hosted Joe Louis fights. The ballroom was on the second floor of the entertainment complex.[1][2][3][4][5]

The 'Renny' was a significant entertainment center during the Harlem Renaissance, and the New Negro Movement in Harlem. When African American culture and art flourished. historically important structure helped usher in the decade-long period of African American cultural and artistic flourishing, which at the time was known as the New Negro Movement. William H. Roach[a] from Antigua, Cleophus Charity and Joseph H. Sweeney from Montserrat were the founding builders of the Renaissance Complex. They were members of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).[4][6]

Developers, owners, and operators[edit]

The African-American owned and operated firm, The Sarco Realty & Holding Company, Inc., raised the funds for the project by selling shares to the public, initially, in February 1920, at 10¢ a share. Sarco's executive directors were William H. Roach, president and general manager; Cleo Charity (1889–1964), vice-president and treasurer; Cornelius Charity, second vice-president; and Joseph Henry Sweeney (1889–1932), secretary. The other directors were John Blake, Edmund Osborne, Shervington Lee, and Edward B. Lynch. Sarco Realty and the R. Holding Company, of which Roach was also President, purchased the land. Sarco contracted Isaac A. Hopper's Sons to erect the Renaissance Theatre building, at a cost of $175,000. Sarco Realty owned and managed the building until 1931. And, Sarco Realty owned and operated the Renaissance Casino and Theatre until 1931.[7]

Original design[edit]

The Renaissance was designed by Harry Creighton Ingalls, who also designed the Henry Miller and Little Theatres in the Theater District. The design was Moorish with glazed tile and palladian windows. The complex had a ballroom, a billiard parlor, stores, and a restaurant called China House. There was a basketball team known as Harlem Rens. The theater had 900-seats and featured movies by Oscar Micheaux, the first African American to produce feature-length films. It was used by the N.A.A.C.P for an Anti-lynching movement meeting in 1923.

Neighborhood of historic jazz venues[edit]

The Renaissance Ballroom was one of several legendary Harlem jazz venues in the 1920s. Others included the Uptown Cotton Club, Connie's Inn, and the Savoy Ballroom. The 'Rennie' was open to African-Americans, while some of the other well clubs in Harlem did not cater to African Americans.[8]

Notable events and mementos[edit]

In 1953, David Dinkins — who served as the first African American mayor of New York from 1990 to 1993 — had his wedding reception at the Renaissance.[9]

In the 1990s, the location was used in Spike Lee's film Jungle Fever as a backdrop for a crack den.[10]

Cessation of operations[edit]

The Renaissance Complex closed in 1979. In 1989, The Renny was purchased by the Abyssinian Development Corporation, an organization established in 1989 as a nonprofit corporation. Abyssinian Development Corporation had planned to restore the 'Renny,' which it did not do.[6] In 1991 attempts were made for the Renaissance to become a landmark by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. It was agreed on but it did not happen.[5]

Recent and current use[edit]

In May 2014 from Abyssinian Development Corporation sold the Renaissance Complex for $15 million.

In 2015 BRP a New York-based developer secured a construction loan from Santander Bank for $53.2 million for the development of a mixed-income residential rental complex. The new building, called 'The Renny,' has an LEED-Silver certification with ecological structure features such as solar panels, a green roof, an energy-efficient boiler and water-saving plumbing[11]

Community criticism of current use[edit]

Prior to commencing the construction of the new Renny in 2015, Harlem residents expressed concerns that the new structure (i) would not improve the African American community in that area of Harlem and (ii) would destroy an important building related to the history of Harlem and an important to the history of the U.S.[12][13]

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^William Howard Roach (surname later also spelled as Roche; 8 September 1881 Plymouth, Montserrat, British West Indies – September 1963 The Bronx) was a Montserratian-born-and-raised-turned-American entrepreneur noted for having been the among the first African-Americans to own real estate in Harlem. Roach led the development and was the founding owner-manager of the Renaissance Theatre which opened in 1921, and its add-on, the Renaissance Casino, which opened in 1923

References[edit]

- ^'The Harlem Renaissance Ballroom,' by Will Ellis, AbandonedNYC (online publication of Will Ellis), May 24, 2012

- ^'Renaissance Ballroom and Casino,' by Michael Henry Adams, Harlem One Stop (a publication of Harlem One Stop Inc., a 501 (c) (3) non-profit organization based in Harlem), January 23, 2007

- ^'A Bid to Save Harlem's Historic 'Renny,'Voices of NY (online publication of the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism), February 6, 2015

- ^ abFirst Black-Owned Theater Faces Uncertain Future,' by Vinette K. Pryce, Caribbean Life News (online publication of CNG Community News Group, Brooklyn), January 30, 2015

- ^ ab'Inside the Abandoned Renaissance Theater and Casino in Harlem,' by AFineLyne (Lynn Lieberman), Untapped Cities – Rediscover Your City (online publication based in Brooklyn), September 2, 2014

- ^ ab'Renaissance Lost: Requiem for a Demolished Harlem Shrine,' by Kevin McGruder & Claude Johnson, citylimits.org, April 17, 2015

- ^'Lafayette and Renaissance Theatres Located in Harlem,' New York Age, February 19, 1921, p. 1 (accessible viaNewspapers.com at www.newspapers.com/image/39621379)

- ^'A Harlem Landmark in All but Name,' by Christopher Gray, New York Times, February 18, 2007

- ^'In Harlem, Renaissance Theater Is at the Crossroads of Demolition and Preservation,' by Kia Gregory, New York Times, December 21, 2014

- ^'Gay Harlem: Renaissance Ballroom and Theater,'Columbia Wikischolars (online collaboration of the Center for Digital Research and Scholarship, Columbia University) (retrieved April 26, 2018)]

- ^'BRP Lines Up $53M Loan for Renaissance Ballroom Site in Harlem,' by Danielle Balbi, Commercial Observer, December 1, 2015

- ^'Harlem Renaissance Site Making Way for Resi Development – 'The Renny' Would Bring 134 Residential Units to West 138th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Blvd.,' Claire Moses, The Real Deal, November 24, 2014

- ^'Renaissance Ballroom: Lost for $1,000,' by Janet Allon, New York Times, January 19, 1997

External links[edit]

Nh Casino Ballroom

- 'Renaissance Theatre' at Cinema Treasures

.jpg)

In 1916, Fort Worth built a Municipal Beach, directly where the Nine-mile Bridge connected to the west shore of Lake Worth. It was a huge success. By 1920, over a hundred thousand bathers patronized the beach each season. It was so popular that a bus line from Fort Worth called the Fort Worth Auto Bus Company took passengers from the end of Rosen Heights line to this beach.

Thanks for helping to make the Casino Ballroom New Hampshire's Premier Entertainment Facility. Get Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom, Hampton Beach, NH, USA setlists - view them, share them, discuss them with other Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom, Hampton Beach, NH, USA fans for free on setlist.fm! Thanks for helping to make the Casino Ballroom New Hampshire's Premier Entertainment Facility. Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom tickets Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom - See it Before it's sold out! Ticketsinventory.com makes it easy to find Sold out Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom tickets in addition to luxury seats for Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom; besides, we are your first destination for New Hampshire hot events appearing in Hampton and your favorite events taking place in Hampton.

In 1927, a company out of Bellafontaine, Ohio called A.J. Miller & Co. wanted to take advantage of this new Lake. Seeing the enormous groups of visitors and bathers that flocked to the Municipal Beach each summer, entrepreneurs, E.A. Albaugh and French Wilgus had a plan to make Casino Park the largest amusement park in Texas and the Southwestern United States. The company leased the very same ground from Fort Worth, and sunk over a $1 million into this playground, which consisted of rides, a midway, a boardwalk, bathhouse and swimming area, and a huge ballroom. Over 125 carpenters were at work at any given time during construction, using more than a million feet of lumber. Casino Park (also known as Lake Worth Amusement Park) would not only cater to bathers and visitors, but would attract oil magnates, wildcatters from west Texas and cattle barons of the Southwest.

Casino Park was renowned for having The Thriller, the largest roller coaster in the southwest. It was almost a mile long, with humps that varied from 14 to 72 feet. Three trains, each carrying 24 passengers were operated. It was one of only three roller coasters in the entire country equipped with the latest safety devices; wheels of the cars rolled between, under and overhead on the track so that a derailment was almost impossible. Mr. H.S. Smith, engineer for the John A. Miller Company of Detroit directed construction of the monster 'ride'. Casino Park also had some unique rides, such as Bluebeards Castle and the 'Bug-a-Boo' tunnel train. Amazing stunts like high diving horses complimented the Midway. There was even a 300-lb caged gorilla named appropriately Big Boy. Other familiar and popular rides such as the 'Tilt-a-Whirl', 'Dodge-em' and Merry-go-round complimented the Park. The Midway had the usual concession stands and games, such as the ring toss and shooting gallery. The park also had the largest boardwalk west of Atlantic City, made of wood and over 400 feet long. A swimming area, complete with a sandy beach and bathhouse drew in those people who wanted to cool off in the summer months. Motorboats could be rented for scenic tours of the lake.

Casino Park held an annual beauty pageant, and on the Fourth of July, the Casino would draw crowds of well over a hundred thousand strong to celebrate and watch the fireworks display put on by the late W.A. Engelke. Mr. Engelke, owner of the Pan American Fireworks Co., in Samson Park, was known throughout the world for his talents in fireworks displays. The park season began each year on May 1st and ended on Labor Day, with bus service that continued to transport the public to this park for several years.

But by far, the center-point and most long-lived attraction was the Casino Ballroom. At over 31,000 square foot, it could seat 2,200 people for dancing and a hot meal for $2 per person, total. It attracted the biggest bands in the country and had it's own nationally known radio show. It had a beautiful smooth floor made of 2-foot x 2-inch strips of solid oak. There were two bars and a full service kitchen. Underneath the ballroom, no space was wasted. On one end, there was an icehouse owned by the Fort Worth Ice Company. On the other side was the boiler room, and in the middle were the tracks of the bug-a-boo train. From the late ‘20s through the ‘50's, the big bands flourished, the top names played at the Ballroom; Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Tommy Dorsey, Glenn Miller, Frank Sinatra, Herbie Kay, Rudy Valle and Ted Weems, to name a few.

Casino Park was also to compete with the Lake Como Pavilion, which had its' pavilion and amusement park rides. But the aging Pavilion, built in 1889 was small and isolated, built more to attract streetcar passengers along the Arlington Heights Line route, and the numbers of people dwindled with the burning of the 'Ye Arlington Inne.' It could not compete with this new and larger amusement park.

The small community of Lake Worth suddenly had a business in it's midst that carried over 500 jobs. The population of Lake Worth wasn't even enough to fill the positions. The population of Lake Worth began to increase as people sought housing close to their place of employment. A land development called 'Indian Oaks' then took off full steam with the help of philanthropist G.T. Reynolds. Each street name featured the name of an indian tribe.

Casino Park was a place that launched many a career. Harry Beason, who grew up in Lake Worth recalls, 'I started off raking the beach sand in the swimming area. Then I was 'promoted' to the icehouse, then the boiler room, both of them under the ballroom. Harry Beason recalls an amusing memory from those days. 'The bug-a-boo cars were driven by mules, and they always seemed to stop in the dark of the tunnel. Couples would take advantage of the dark to become romantically involved. It was my job to prod the mules so that the ride wouldn't back up'. Interestingly enough, Beason became Sheriff of Lake Worth in his later years.

Life began for Constable Paul Meador when he was nine years old. That's when his family moved from the sleepy community of Azle to Lake Worth. With the Parks' boardwalk, roller coaster, rides and dance hall, he remininced in an interview for the 1984 Sentinel: 'It was like living in a carnival. What kid wouldn't like it?'.

Another resident, Bud Irby, began as a busboy in the ballroom, and eventually became a partner in the Lake Worth Amusement Company, the owners of Casino Park.

The 1920's

The first manager for Casino Park was E.L. Furnas, and he had his hands full.

In only it's second season, Fire destroyed much of the Park in 1928. On June 17th , 6:20 a.m., fire followed a blast on the boardwalk. Fanned by high winds blowing off the lake, it quickly got out of control of park employees, who attempted to stem destruction with four chemical carts. A dozen fire trucks which raced to the scene, pumped water directly from the lake and succeeded in saving Bluebeards' Castle and the Thriller. The Ballroom, bathhouse and between 25 and 30 concessions were destroyed. Four park employees, attempting to save the ballroom, were trapped and forced to leap into the lake and swim to safety. Big Boy, the 300-lb gorilla, was burned to death. Workers described as almost human the weird cries of the giant beast as flames licked into his cage. 'You could hear the screams of the gorilla for miles' recalls one of Effie Morris' students. Fortunately, the gorilla was given a mercy killing. A cause for the fire was never determined. It must have not been for the insurance, because A.J. Miller & Co went right back, reconstructing Casino Park from the ground up. It cost $140,000 to rebuild. But as rebuilding took place, Mr. Furnas decided to leave Casino Park forever.

The company needed a new manager replacement. Stockholders from the A.J. Miller Company, who had known Smith, asked him to take charge So in the same year, George T. Smith moved to Fort Worth from Los Angeles to take over operations of the Casino Ballroom. In Los Angeles he had been a salesman for ambulances and funeral hearses. . It was quite a career change, switching from the macabre to a rainbow world of dance bands and nighttime merriment.

The Casino Ballroom flourished in the 1920s' with the big bands. The first band to play at the Casino Ballroom was headed by Hogan Hancock. Hancock had a trumpeter in the band that blew with such gusto that Casino owner George Smith found it intolerable. Completely unnerved by the trumpeter's blasts, he gave sharp orders to Hancock: 'You either put that trumpeter in the back row of the band or hide his horn. He's driving me nuts!'. Hancock hastily moved the offending trumpet to a chair completely behind the band. Not too many years later, G.T. Smith was glad to have this young trumpeter back at the Casino, and to pay him a large fee. This time, the trumpeter was heading his own band, and was a star. His name: Harry James!

The 1930's

The park reopened on June 28th, 1930. But instead of being built primarily with wood, many of the major structures were built in a stucco Mediterranean style motif. The 1930's were the heyday for this park, despite the Great Depression of 1929. People who had money, spent it.

Many nightclubs opened along the stretch of Jacksboro Highway, trying to compete with Casino Park. A young lad could make a small fortune in those days, running bottles of whisky to customers at 50 cents each. It was possible to earn $150 a week - a small fortune in those days (roughly the equivalent of $900 today). Women were 50 cents each, or $2 for the night - and plentiful. Although booze and gambling were illegal, either by state or federal law, the strip boomed. The practices were general knowledge, even to law enforcement officials. But rarely would a business be closed; conveniently, somehow the slot machines and booze would ‘disappear' from an establishment as watching eyes loomed nearby. As these businesses flourished, so did the gambler and gangster activity. Jacksboro Highway was beginning to get a reputation.

Nightclubs with exotic names such as The Palm, The Blue Dragon Inn, The Peacock Garden, Gingham Inn, The Showboat, and the Yellowjacket began to dot Jacksboro Highway, creating a strip leading out of Fort Worth. Many if not all of these clubs offered booze and gambling. The establishments were a medley of honky-tonks and high-class establishments, catering to the elite, bootleggers, rogues, rednecks, roughnecks and college kids on the prowl.

The Coconut Grove Nightclub was opened by Earl Hodgkins, son of Jim Hodgkins in 1937, on the same ground where the old Hodgkin's Trading Post was located. Free internet live tv. It is located where the old Coconut Grove Beer Barn stood, at Jacksboro Hwy and Foster. The Coconut grove was the place of choice for musicians to congregate after completing their gigs.

But the Casino Ballroom had to be held above regard. The best of the best performed there. It wasn't just a matter of 'no shoes, no shirt, no service. You had to wear a coat and tie in the ballroom, and ladies wore dresses. And it wasn't a place to fight. To insure this, a group of bouncers headed by former heavyweight boxer Sully Montgomery maintained the peace. Sully was a big man, the toughest of the tough. It was a common sight to see him at the 'ringside' at the end of the boardwalk for monday night boxing. He later became Tarrant County sheriff from 1946 to 1952.

The 1940's

The 1940's were to become the decline of Casino Park. The years of depression were beginning to wear out even the staple customers. Numerous fights between the Casino, the City of Fort Worth and even the State of Texas were more the norm than the exception, With World War II, the casino operated profitless during the winter seasons at the request of the military authorities.

The year 1940 in particular was not a good year for the park. As early as February 6th , Casino Park sought debt relief in court. Then tragedy struck: on the July 4th , 1940 11 p.m., a portion of the boardwalk collapsed, injuring 56 people, 8 seriously. On the same day, a drunk made a fatal mistake and stood up in the roller coaster, falling out as it came out of the apex of the circular ‘loop' of the Thriller. Independence Day was one of the busiest days of the season. The news spread like wildfire, seriously damaging the reputation of the park.

By July 26th, the Casino was to fill out it's season under receivership to avoid shutdown threatened under a temporary injunction obtained by the State Comptroller's office in Austin. It restrained the resort from operating until it had purged itself of $2000 in back taxes. By August 9th, the Casino Park was in bankruptcy. A hearing was conducted for casino manager G.T. Smith. All in all, 22 misdemeanor accounts were filed against him, including operating slot machines without a license. But business went on; by year's end, the City of Fort Worth and G.T. Smith had reached a lease agreement. Casino Park struggled on. G.T. Smith remained until 1949.

By 1941, the boardwalk was torn down. The contract was awarded to Morrow Wrecking Company for $3,250.

On April 8th, 1943, fire destroyed the bathhouse, reducing it to ashes. A cause for the blaze was never determined. Replacement costs were estimated at $15,000, and the city, which now owned the property, had only $6000 insurance on the structure. It was decided not to replace the structure, mainly because it had not been used in quite some time. The Bathhouse had been in a dilapidated condition, with windows broken out and wood boards removed. With the bathhouse destroyed, operation of the beach and swimming area was in jeopardy. On April 16, 1947, Fort Worth took over.

The legal and economic woes for Casino Park continued. On May 21, 1947, the City of Fort Worth filed suit against the Park for delinquent back taxes in the order of $6,917. Smith said that an investigation of the city tax records showed that the Casino was not assessed any taxes between 1938 and 1945, but the city legal department on April 30 had back payments assessed until 1938. Smith said he received only one tax statement, for taxes due in 1946 that he paid.

Asst City Attorney Floore said, 'There were delinquent taxes due at the time the suit was filed in district court on which he had notice.' Floore said the 1946 taxes were not paid until Wednesday; $765.05 in taxes plus $45.90 in penalties. Said Floore: 'If Mr. Smith will pay the taxes owing, the city will dismiss the suit.'

The reputation of Jacksboro highway began to tarnish along the neon 10-mile strip rough-and-tumble, now known as 'Thunder Road'. As a youngster growing up on Jacksboro Highway, Pat Kirkwood scrambled atop the roof of his dad's gambling joint on Saturday nights and assessed the economy by activities along the road below. 'If it was a three ambulance evening, money was a little tight', he recalled. 'but seven or eight ambulances meant everything was OK. People were out spending money and boozing and brawling'.

The Casino Ballroom still survived, with Woods Moore leading the Casino Ballroom orchestra In 1945. In 1948, G.T. Smith retired from Casino Park and ownership was maintained by the City of Fort Worth. Joe E. Landwehr managed the Park for the city until it could find a new owner. Joe Landwehr named Wayne Karr to head the Casino orchestra.

In the spring of 1949, a Trans-Texas airliner having mechanical problems made a crippled landing at Meachum Field. The passengers were informed that there would be a delay of several hours. The unexpected stop was to change the life of one passenger aboard. This passenger was en route from his Alpine, Texas auto dealership to watch the Alpine Cowboys play a baseball game in Wichita, Kansas. The passenger: Jerry Starnes. As he recalled: 'I had heard of Fort Worths' Lake Worth Casino Ballroom and decided I'd like to see it. I took a cab from the airport to see the Casino.' As Starnes arrived, he said 'The ballroom was impressive but I was shocked by the condition of the adjacent lake beach. The old bathhouse was about to fall down. It was a junkyard' Starnes was captivated by the possibilities of a newly equipped beach with side attractions. So much, in fact, he stayed over in Fort Worth, went to city hall and signed a lease to take over Casino Beach.

Starnes gave Casino Beach and the Ballroom a 'second wind.' As Casino Beach began it's first season under Starnes, Ray McKinleys' band played to big crowds at the Casino Ballroom. Told of Glenn Miller being coaxed into that fatal flight by a playboy flyer from New Orleans, McKinley remarked, 'The weather was terrible. Even the birds were walking that day'.

Tommy Dorsey drove up to the Ballroom on Oct 17th, in his newest pride, a $40,000 luxury bus. On tour with his band, Dorsey was living on the bus. His bedroom on this land yacht included a mobile phone, radio and an icebox filled, not with the expected beer, but cans of tuna - tuna sandwiches were his passion. He and his band played that night at the Ballroom. He played 'I'm getting sentimental over you'.

The 1950's

The 1950's gave the Casino Ballroom a run for it's money. As television gained popularity, it slowly ushered out the era of the Big Bands. A new formal opening was given by State Senator Keith Kelly in June 1952. He recalled the pleasures of the old boardwalk and called attention to the new safety features for the new one. The paved quarter-of-a-mile boardwalk is fireproof and will not collapse. Jerry Starnes described the shooting gallery, miniature golf course, roller coaster and mini-train for children. But these were never built.

The 1950's were the apex for gangster activity, with Jacksboro Highway as the center of attention. A 'boot hill' in Lake Worth was an exit for many a gambler or gangster.

Jerry Starnes also had his hands full with lawsuits and squabbles with the City of Fort Worth. In December 1958, when Starnes asked for a new 10-year lease to operate Casino Beach, the City Counsel criticized the operation of Casino Beach operations, and demanded to see their books. They also criticized the city auditing department for not keeping the counsel informed when the concessionaire got into arrears with rent. The company owed the city about $11,000 in back rent and concessions percentages. No rent had been paid since 1953.

The 1960's

The 1960's proved a lull for Casino Beach, and the Lake Worth area. One of the financial partners, Bud Irby, had left the Casino Ballroom after many years and established a 20,000 square foot ballroom on the South Freeway (I-35) called 'Guys and Dolls'. Within a year, the Casino Park owners were looking to sell. Sell they did, and the Ballroom stayed alive in various forms, with music leaning to popular ethnic varieties.

In 1965, the Casino Ballroom was remodeled at a cost of $90,000.

At it's height, the Casino Ballroom covered 31,000 square feet, and 2200 people could sit down for a hot supper and dance to the big bands for $2 per person. But rock and roll bands changed the game. Their fees made it impossible to break even with 2200 people. In fact, it would have required seven or eight thousand people to make the break even point. The break-even areas became coliseums and stadiums. Lake Worth had little to offer. Its entertainment attractions were gone. Its recreational status had been superceded by Eagle Mountain and Benbrook Lakes.

The 1970's

Last tango at the Casino: January 31, 1973

The wrecking of Fort Worth's storied Casino Ballroom began yesterday, with workmen in hard hats first ripping away parts of the roof. Then at 4:30 p.m., when debris rained down from the ceiling had covered much of the dance floor, Jerry Starnes and his partner, Reba Smith, danced what had to be the last dance at the Casino. It was a tribute to the thousands of couples who danced away dreamy hours at this nationally known ballroom on Lake Worth. Empty and stripped of it's carpeting was the Casinos' bandstand where the most recognized bandleaders in the country had stood.

Overhead, workmen from the Hearne Wrecking Lumber Company had already torn away enough of the roof so that sunlight intruded on parts of the dance floor that only the twin rotating crystal balls had overseen for decades. The dappled, multi-colored lights spelled romance.

The Hearne Wrecking Lumber Company estimated that it will take five weeks to complete razing of the Casino Ballroom, which had been ordered by the City of Fort Worth. As the roof was torn away, heavy wooden girders beneath looked almost brand new. Workers were amazed. All salvaged lumber was sold on the spot.

Starnes revealed that the Casino may have been saved had not Dan Blocker, the Hoss Cartwright of TV's 'Bonanza' died last May. Mr. Blocker was prepared to put up $250,000 for repairs to the Ballroom, including costly fire-prevention provisions required by the City of Fort Worth before it would lease the Casino.

Starnes knew Blocker when the TV star-to-be was just a student. Starnes aided Blocker, and two became friends for life. Starnes said, 'I talked with Dan on the phone tree weeks before his sudden death. He planned to fly to Fort Worth for a look at the Casino. He was ready to put up the money. Dan had so much money he had no idea what he was worth. He was a millionaire several times over'.

H Casino Ballroom Seating Chart

To put a final nail in the coffin, G.T. Smith died at the age of 85, outliving the Casino Ballroom by one week. But in retirement, he was not one to dwell in the past. When demolition of the Ballroom began, hundreds flocked to the site for a 'last look' at the ballroom where they had danced away happy hours in younger years. Not G.T. Smith, however. From his home at 3815 West 4th Street, he told Jack Gordon, Fort Worth Columnist, 'I'm not a sentimentalist. No, I won't be going out to the Casino again, ever'. He never did.

Casino Park Inc. Managers

E.C. Furnas, 1928

George T. Smith, 1928-1949

Jerry Starnes, 1949-1973

Joe E. Landwehr, 1959-1966

| Former names | R'naissance Casino Ballroom (1926) |

|---|---|

| Address | 2341–2349 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard Harlem |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1924 |

| Closed | 1979 |

| Demolished | 2015 |

| Architect | Harry Creighton Ingalls |

The Renaissance Ballroom & Casino was originally, when built in 1921, a New York City complex that included a casino, ballroom, 900-seat theater, six retail stores, and a basketball arena. It was located in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan at 2341–2349 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, on the east-side of the boulevard between 137th and 138th Streets. The 7th Avenue frontage spanned the entire block.

History[edit]

The Renaissance Theatre Building, as it was originally named, opened January 1921. It was built and owned, until 1931, by African Americans. It was known as the 'Rennie' and was an upscale reception hall. The 'Renny' held prize fights, dance marathons, film screenings, concerts, and stage acts. It was also a meeting place for social clubs and political organizations in Harlem. They gathered to dance the popular dances at the time, the Charleston, Lindy Hop, and Black Bottom, to live music performed by well known jazz musicians. Jazz artists such as Louis Armstrong, Fletcher Henderson, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Lionel Hampton, Cootie Williams, Bessie Smith, Lena Horne, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald performed at the 'Renny'. In the 1920s the Renaissance Ballroom was known as a 'Black Mecca'. It hosted Joe Louis fights. The ballroom was on the second floor of the entertainment complex.[1][2][3][4][5]

The 'Renny' was a significant entertainment center during the Harlem Renaissance, and the New Negro Movement in Harlem. When African American culture and art flourished. historically important structure helped usher in the decade-long period of African American cultural and artistic flourishing, which at the time was known as the New Negro Movement. William H. Roach[a] from Antigua, Cleophus Charity and Joseph H. Sweeney from Montserrat were the founding builders of the Renaissance Complex. They were members of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).[4][6]

Developers, owners, and operators[edit]

The African-American owned and operated firm, The Sarco Realty & Holding Company, Inc., raised the funds for the project by selling shares to the public, initially, in February 1920, at 10¢ a share. Sarco's executive directors were William H. Roach, president and general manager; Cleo Charity (1889–1964), vice-president and treasurer; Cornelius Charity, second vice-president; and Joseph Henry Sweeney (1889–1932), secretary. The other directors were John Blake, Edmund Osborne, Shervington Lee, and Edward B. Lynch. Sarco Realty and the R. Holding Company, of which Roach was also President, purchased the land. Sarco contracted Isaac A. Hopper's Sons to erect the Renaissance Theatre building, at a cost of $175,000. Sarco Realty owned and managed the building until 1931. And, Sarco Realty owned and operated the Renaissance Casino and Theatre until 1931.[7]

Original design[edit]

The Renaissance was designed by Harry Creighton Ingalls, who also designed the Henry Miller and Little Theatres in the Theater District. The design was Moorish with glazed tile and palladian windows. The complex had a ballroom, a billiard parlor, stores, and a restaurant called China House. There was a basketball team known as Harlem Rens. The theater had 900-seats and featured movies by Oscar Micheaux, the first African American to produce feature-length films. It was used by the N.A.A.C.P for an Anti-lynching movement meeting in 1923.

Neighborhood of historic jazz venues[edit]

The Renaissance Ballroom was one of several legendary Harlem jazz venues in the 1920s. Others included the Uptown Cotton Club, Connie's Inn, and the Savoy Ballroom. The 'Rennie' was open to African-Americans, while some of the other well clubs in Harlem did not cater to African Americans.[8]

Notable events and mementos[edit]

In 1953, David Dinkins — who served as the first African American mayor of New York from 1990 to 1993 — had his wedding reception at the Renaissance.[9]

In the 1990s, the location was used in Spike Lee's film Jungle Fever as a backdrop for a crack den.[10]

Cessation of operations[edit]

The Renaissance Complex closed in 1979. In 1989, The Renny was purchased by the Abyssinian Development Corporation, an organization established in 1989 as a nonprofit corporation. Abyssinian Development Corporation had planned to restore the 'Renny,' which it did not do.[6] In 1991 attempts were made for the Renaissance to become a landmark by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. It was agreed on but it did not happen.[5]

Recent and current use[edit]

In May 2014 from Abyssinian Development Corporation sold the Renaissance Complex for $15 million.

In 2015 BRP a New York-based developer secured a construction loan from Santander Bank for $53.2 million for the development of a mixed-income residential rental complex. The new building, called 'The Renny,' has an LEED-Silver certification with ecological structure features such as solar panels, a green roof, an energy-efficient boiler and water-saving plumbing[11]

Community criticism of current use[edit]

Prior to commencing the construction of the new Renny in 2015, Harlem residents expressed concerns that the new structure (i) would not improve the African American community in that area of Harlem and (ii) would destroy an important building related to the history of Harlem and an important to the history of the U.S.[12][13]

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^William Howard Roach (surname later also spelled as Roche; 8 September 1881 Plymouth, Montserrat, British West Indies – September 1963 The Bronx) was a Montserratian-born-and-raised-turned-American entrepreneur noted for having been the among the first African-Americans to own real estate in Harlem. Roach led the development and was the founding owner-manager of the Renaissance Theatre which opened in 1921, and its add-on, the Renaissance Casino, which opened in 1923

References[edit]

- ^'The Harlem Renaissance Ballroom,' by Will Ellis, AbandonedNYC (online publication of Will Ellis), May 24, 2012

- ^'Renaissance Ballroom and Casino,' by Michael Henry Adams, Harlem One Stop (a publication of Harlem One Stop Inc., a 501 (c) (3) non-profit organization based in Harlem), January 23, 2007

- ^'A Bid to Save Harlem's Historic 'Renny,'Voices of NY (online publication of the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism), February 6, 2015

- ^ abFirst Black-Owned Theater Faces Uncertain Future,' by Vinette K. Pryce, Caribbean Life News (online publication of CNG Community News Group, Brooklyn), January 30, 2015

- ^ ab'Inside the Abandoned Renaissance Theater and Casino in Harlem,' by AFineLyne (Lynn Lieberman), Untapped Cities – Rediscover Your City (online publication based in Brooklyn), September 2, 2014

- ^ ab'Renaissance Lost: Requiem for a Demolished Harlem Shrine,' by Kevin McGruder & Claude Johnson, citylimits.org, April 17, 2015

- ^'Lafayette and Renaissance Theatres Located in Harlem,' New York Age, February 19, 1921, p. 1 (accessible viaNewspapers.com at www.newspapers.com/image/39621379)

- ^'A Harlem Landmark in All but Name,' by Christopher Gray, New York Times, February 18, 2007

- ^'In Harlem, Renaissance Theater Is at the Crossroads of Demolition and Preservation,' by Kia Gregory, New York Times, December 21, 2014

- ^'Gay Harlem: Renaissance Ballroom and Theater,'Columbia Wikischolars (online collaboration of the Center for Digital Research and Scholarship, Columbia University) (retrieved April 26, 2018)]

- ^'BRP Lines Up $53M Loan for Renaissance Ballroom Site in Harlem,' by Danielle Balbi, Commercial Observer, December 1, 2015

- ^'Harlem Renaissance Site Making Way for Resi Development – 'The Renny' Would Bring 134 Residential Units to West 138th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Blvd.,' Claire Moses, The Real Deal, November 24, 2014

- ^'Renaissance Ballroom: Lost for $1,000,' by Janet Allon, New York Times, January 19, 1997

External links[edit]

Nh Casino Ballroom

- 'Renaissance Theatre' at Cinema Treasures